14 Jan Why Long Island City Often Feels Colder Than Manhattan

Why Long Island City Often Feels Colder Than Manhattan

Introduction

If you’ve ever stepped off the subway in Long Island City (LIC) during the winter and thought “Why does it feel colder here than Manhattan?” — you’re not alone. Despite being just across the East River from Midtown, LIC often feels significantly colder and windier than parts of Manhattan. The difference isn’t just in perception — a combination of geography, climate patterns, and urban design creates distinct microclimates between the two neighborhoods.

Water, Wind, and the Waterfront

Long Island City sits directly on the East River, exposing it to cold air that sweeps in across the water. Water holds onto cold longer than land, and during the winter months the river acts almost like a conveyor belt of chill. Winds blow unimpeded off the river and into LIC’s streets, amplifying the felt temperature through a natural wind chill effect.

Residents often comment on these stronger gusts, especially near the waterfront and tall buildings — a real-world example of how wind corridors can form through urban design (and yes, many LIC locals do notice this phenomenon every day).

Wind Tunnels and Urban Geometry

Tall, modern high-rises in LIC do more than offer great skyline views — they shape airflow. When wind moves between closely spaced tall buildings, it accelerates, creating a wind tunnel effect. This can make the environment feel much colder than official air temperature readings might suggest.

Manhattan’s older street grid and varied building heights often act as natural windbreaks, slowing gusts and shielding pedestrians from the full force of waterfront breezes.

Urban Heat Island: Manhattan’s Unintended Warm Blanket

One of the key reasons Manhattan often feels slightly warmer than LIC is the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect — a scientifically documented climate phenomenon where dense urban areas trap and re-radiate heat. Manhattan’s dense streets, heavy traffic, underground subway system, and towering buildings store heat throughout the day and slowly release it at night, keeping the area warmer.

This effect is particularly pronounced in big cities: research shows that cities like New York can feel up to 9–10°F warmer than surrounding areas due to heat absorbed and retained by urban infrastructure.

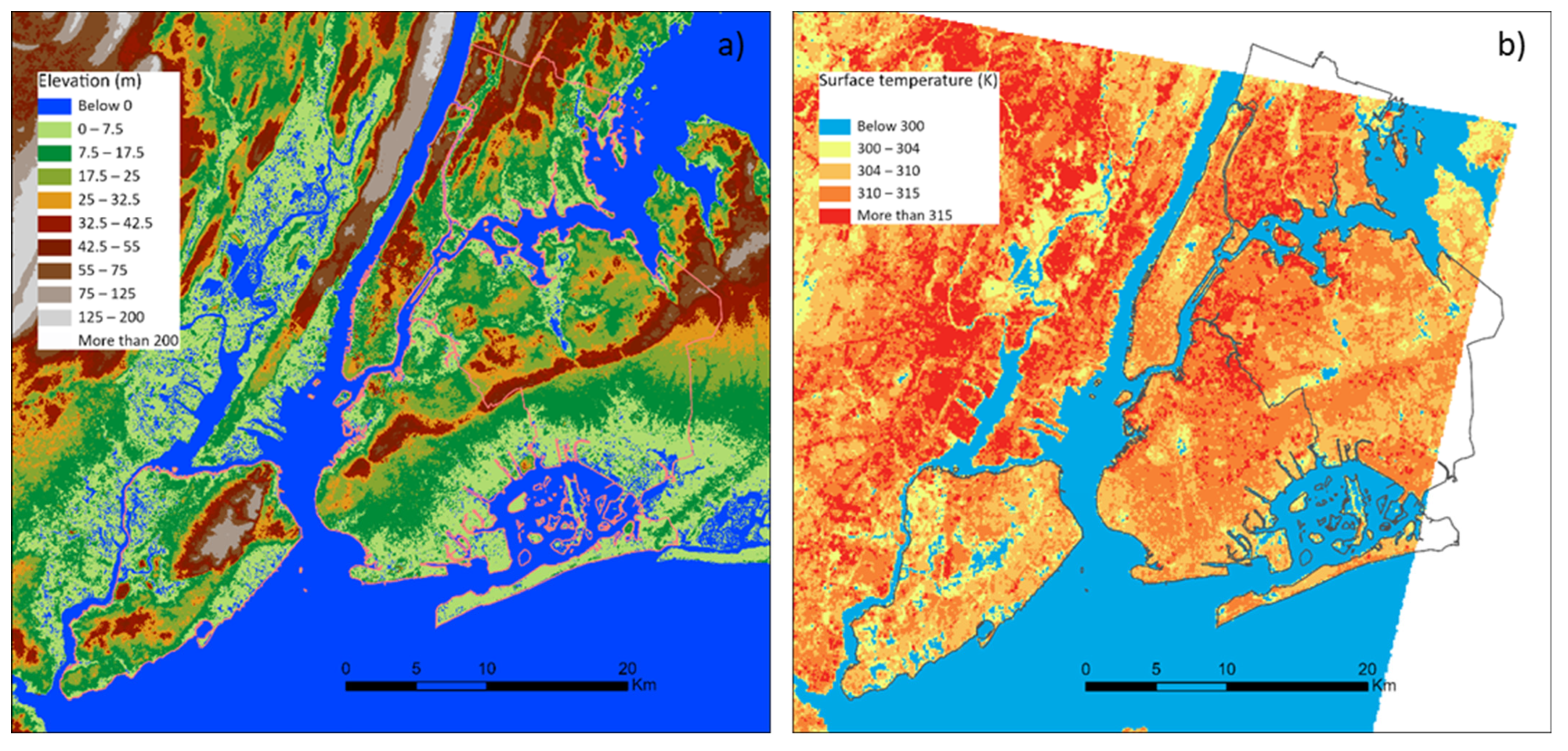

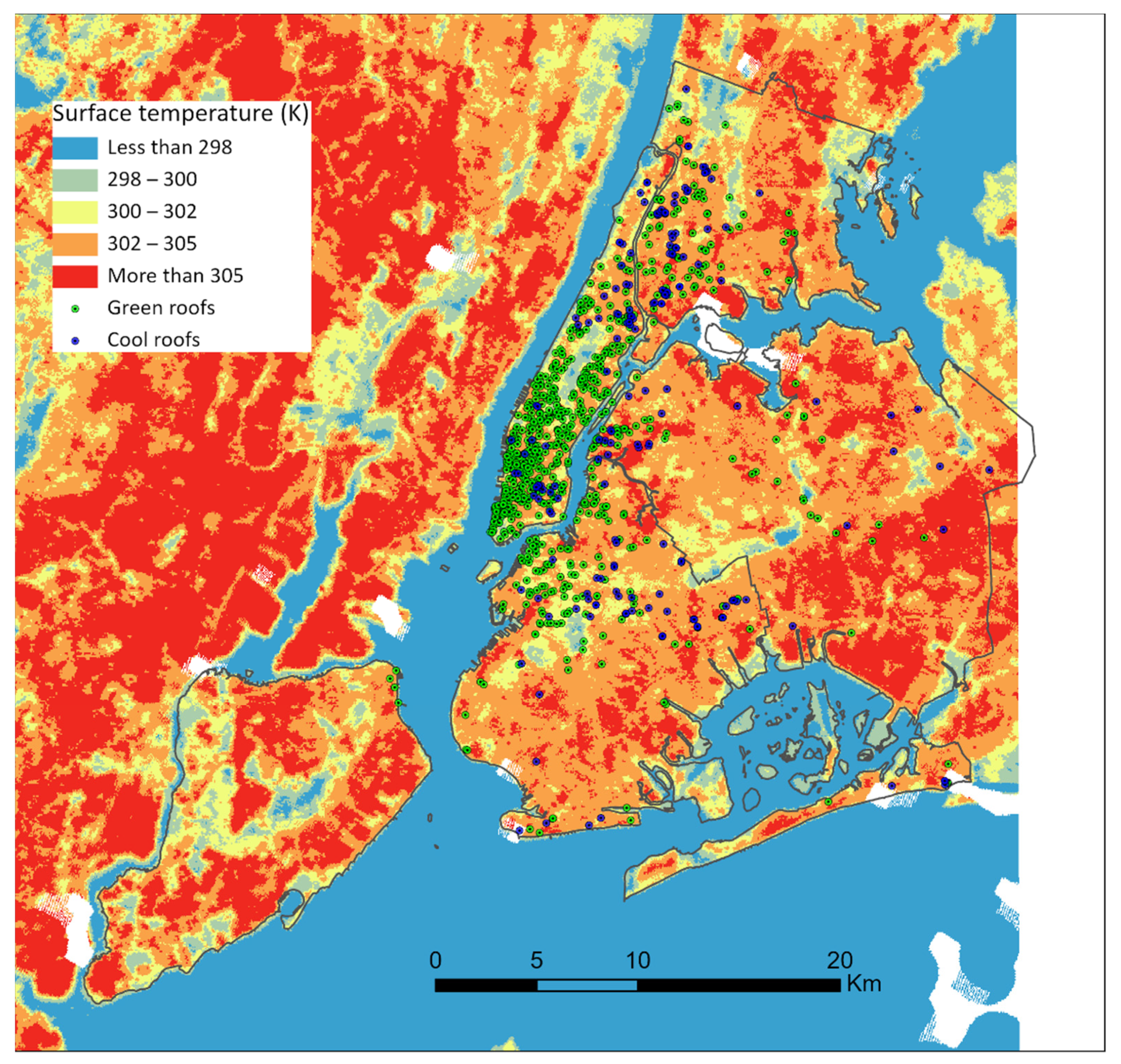

The map visuals above highlight how urban materials, building density, and reduced vegetation change local surface temperatures — with deep color variations showing warmer areas relative to cooler ones near water or green spaces.

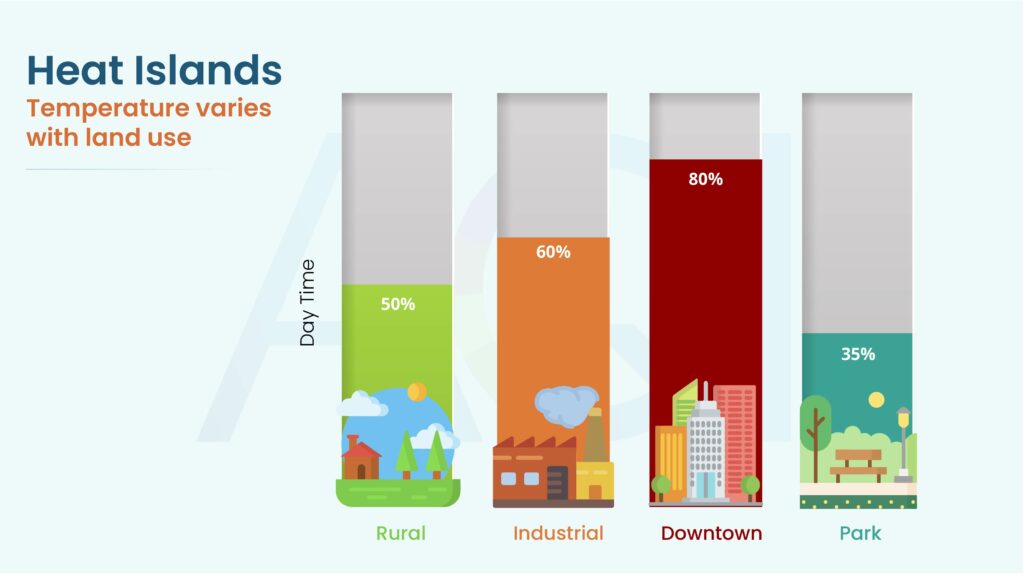

Urban Heat Island Chart

Below is a conceptual scientific chart that explains how different environments retain heat overnight — useful for understanding why LIC’s lower density and proximity to water contribute to a colder microclimate:

This type of graph illustrates how temperature varies by land use — rural, industrial, downtown, and suburban — during day and night. City centers retain more heat through the night, while waterfront and less developed areas cool faster as soon as the sun sets.

Faster Cooling and Less Nighttime Retention

LIC doesn’t have Manhattan’s extensive underground infrastructure — subway tunnels, basements, and decades of human activity that contribute to nighttime warmth. Instead, LIC’s streets and buildings cool rapidly after sunset, making evenings chillier, especially when combined with wind off the river.

This becomes most noticeable in winter when the days are short, and both neighborhoods lose heat quickly once the sun goes down.

Additional Scientific View: Surface Temperatures Around NYC

Here’s a scientific satellite surface-temperature chart showing how land cover and development influence heat on a broader scale:

Satellite studies like this use infrared data to show surface temperature variations across New York City, revealing patterns that correspond with human development, green spaces, water bodies, and built environments. Urban cores tend to appear warmer due to heat retention, while open areas, water, and parks — like those near LIC — appear cooler.

Psychological and Perceptual Factors

There’s also a psychological component to the perception of cold. Many people travel from heated subway platforms, enclosed indoor environments, and thicker building walls in Manhattan directly into LIC’s open, wind-exposed streets. That sudden transition makes the cold feel more intense than walking outdoors in Manhattan.

Why It Matters to Residents

For LIC residents and newcomers, these microclimatic differences aren’t just trivia — they shape daily life:

- Clothing choices: Residents often bundle up earlier in winter than Manhattan commuters.

- Outdoor activity planning: Waterfront parks and plazas feel chillier much earlier in the season.

- Urban planning discussions: Wind mitigation, street canyons, and waterfront design are frequent topics in community discussions.

Conclusion

Long Island City’s chillier feel compared to Manhattan isn’t a trick of the mind — it’s rooted in physics, geography, and the way cities interact with air and heat:

- Water and wind deliver a persistent cooling influence.

- Urban geometry accelerates wind chill in LIC.

- Manhattan’s dense infrastructure traps heat, moderating cold.

- Nighttime heat retention differences enhance the contrast.

Together, these factors create a distinct microclimate in LIC — one that feels colder and crisper than just a few blocks away in Manhattan.

No Comments